They Were Here

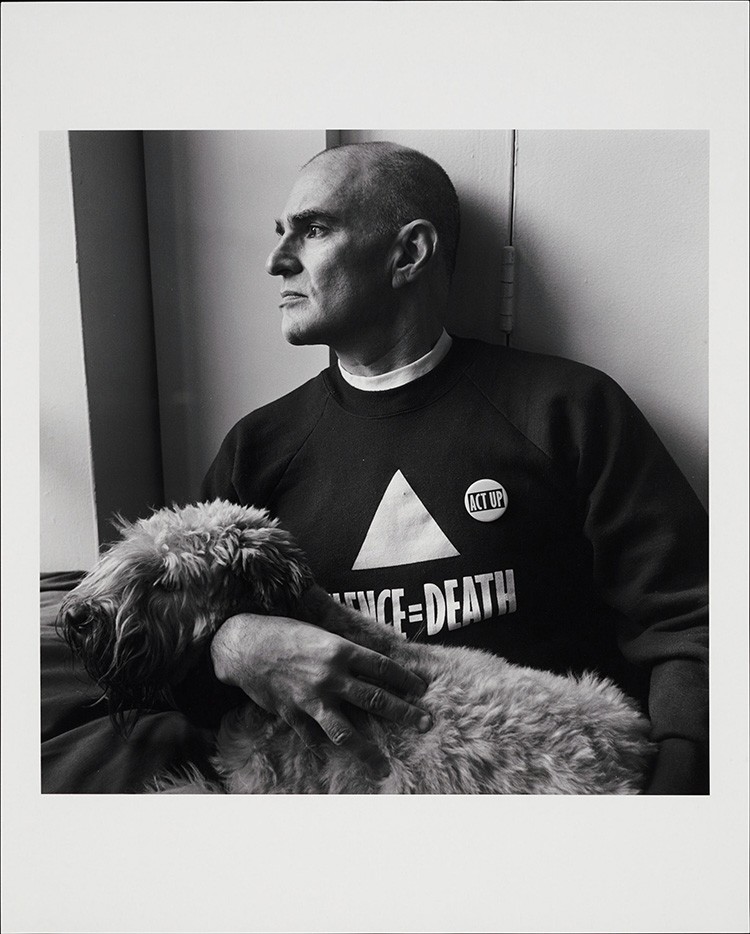

As I write this, we are in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. No one knows how it will end, or when. But it seems eerily appropriate to recall that nearly 40 years ago, the world suddenly faced another unidentified virus that threatened to spread worldwide. Within a remarkably short time, that virus invaded every continent—minus, one suspects, Antarctica. Several years into the HIV/AIDS pandemic, the American photographer Robert Giard (1939–2002) saw in quick succession two plays dealing with the depredations inflicted by the illness. He wrote of attending Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart: “[W]atching the play unfold in the darkened space of the arena-style theater, its walls inscribed with the names of the dead, some of which I recognized, I was moved to a sense of urgency.” He had “a renewed consciousness of the historical indignities which gay people have encountered,” he wrote, “and a further reminder that my own days could prove briefer than most of us are accustomed to anticipating.” Several weeks later, attending a performance of As Is by William M. Hoffman, Giard was confirmed in his intention “to attach whatever skill or insight I might possess to an overly gay/lesbian theme.” Although he had always photographed creative and intellectual friends across the broad spectrum of sexualities, now he began to imagine “a sustained body of work that chronicled a significant aspect of gay life.”

The result was his more than two-decade project Particular Voices: Portraits of Gay and Lesbian Writers, which grew to encompass some 600 photographs of LGBTQ writers across disciplines: poetry, journalism, fiction, nonfiction, playwriting, historical and cultural scholarship, performance art, publishing, and activism. Giard’s portraits were published as a monograph in 1997, and were exhibited at the New York Public Library the following year; this spring, the Leslie-Lohman Museum in New York mounted a new exhibition of Giard’s work, indicating just how resonant his project remains. The Robert Giard Foundation, established after his death, still awards a yearly grant in photography in partnership with Queer | Art. Given the recent retrospectives and restoration of queer photographers with wildly varying styles—among them, David Wojnarowicz, James Bidgood, Alvin Baltrop, and Peter Hujar—Giard’s work reminds us how indelible and moving a simple portrait can be.

I met Giard in the summer of 1979, when he was living year-round with his partner, Jonathan Silin, in the beach community of Amagansett, Long Island, in a modest house off a long drive on one of the town’s residential streets. That summer, I was a resident at the Edward Albee Foundation on Long Island’s far eastern end where the fishing village of Montauk was beginning to attract a hip young crowd. Up the hill from the harbor, the author of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? had established a residency grant for visual artists and writers to live for a time on his property. One day, as I headed for the “gay beach” via jitney service, a chance meeting with a successful writer of lesbian pulp novels of the 1950s got me invited to a local gay/lesbian political association’s Friday night get-together—EEGO, the East End Gay Organization. I met Giard at that event. We found common ground in my research on the history of the male nude in photography—a genre Giard had himself taken up—and in a few photographer and writer friends we both knew.

Giard was modest, with a reserved manner, although to say so suggests he was without ego. He was confident in his work and labored methodically and diligently at it. Beyond his formal education and his degrees he was a person of wide cultivation. He knew a great deal about the history of photography, about cinema, about the opera, but he wore his knowledge lightly. He never hammered you with his brilliance because he carried himself as one among equals. We enjoyed talking movies and movie stars, photography, and contemporary literature. If I was staying at the Amagansett house, we might pass a good hour after breakfast just shooting the breeze about gay culture, American culture, film culture, TV culture, and what personality or actor of late was worth more than a second look. We laughed a lot. It was a pleasure to be silly with him and abandon any pretense of being “intellectual.” He was a gentle man, and a gentleman, and an avowed feminist with many women friends and colleagues. I never heard anyone say a word against him.

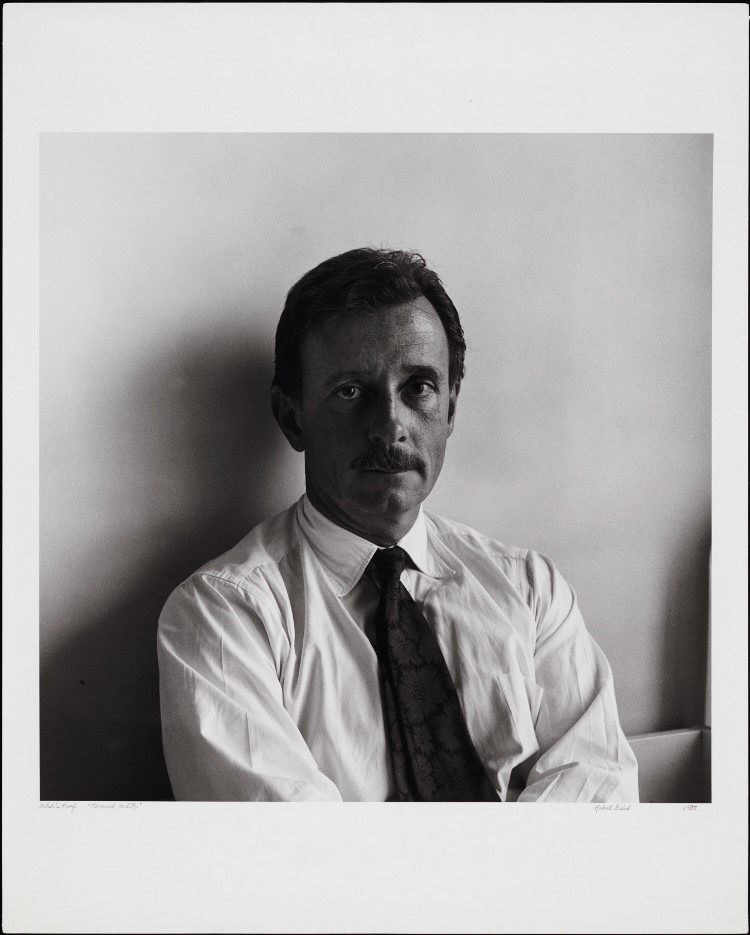

Particular Voices built slowly as he set out on a documentary task whose epic outlines he could then only guess. He inaugurated the project with portraits of Kramer and Hoffman, whose plays had so moved him. Giard, an avid reader with a BA in English and American literature from Yale, and an MA in comparative literature from Boston University, gladly read the work of the writers he photographed, often on the recommendation of other gay and lesbian writers who had sat for his camera. Early on, he photographed Edmund White who, by the mid-1980s, had advanced among the seven members of the Violet Quill group (a cadre of gay writers in New York) to the front rank of literary gay fiction. Giard had a sitting with White, who was in New York from his expat residence on Paris’s Ile Saint-Louis in order to promote his recently published novel Caracole (1985).

When I was leaving New York to live in Paris for a half-year in 1986, Giard entrusted me to deliver a print of the portrait to White. It was a beautiful and unadorned vision of the writer, still youthful in the first stages of middle age. White sits against an empty wall, the barest hint of a smile beneath a rakish mustache. Trim and well groomed, the writer wears an ample white shirt and a dark floral-patterned tie. The stark wall behind him is softly shaded by his shoulders and torso. The picture is compositionally austere: man, face, wall. And yet so intent is White’s expression that we get lost in his soulful gaze.

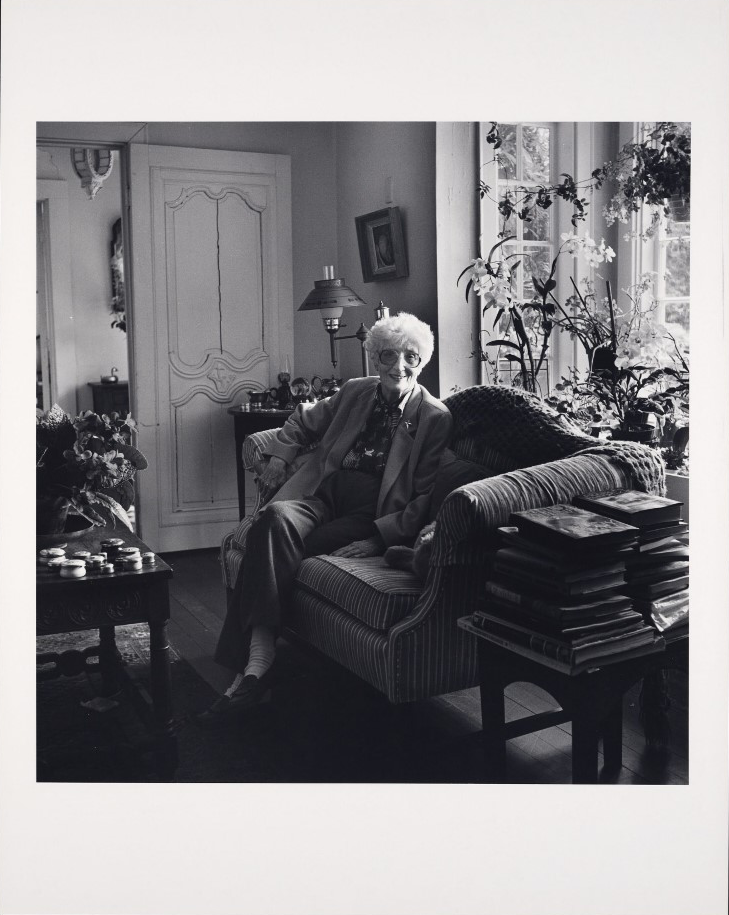

This would be one of Giard’s principal modes and suggests the influence of the German portraitist August Sander, who often shot various Prussian “types” in a like declarative mode in the decades before WWII. Giard’s portraits of Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, Bruce Boone, J.D. McClatchy, and others follow a similarly unembellished style. An alternative approach is Giard’s environmental portrait, in which the subject is surrounded by the décor and trappings of a familiar interior. His photographs of Kevin Killian, Mark Doty, James Purdy, and Gary Indiana, for example, offer glimpses of variously bookish or disheveled domestic backdrops. His richly detailed 1994 portrait of poet, novelist, and memoirist May Sarton has her cozy on a couch in her home in York, Maine, the year before her death at age 83. She is surrounded by two neat piles of oversized books on a low end table, by hanging plants and lavish sprays of flowers that seem to spread inside from beyond the tall open window behind her, and by glimpses of solid furniture displaying ornamental curios. A Persian carpet lays just past the soles of her shoes. The aging writer is splendidly neat in her slacks, patterned blouse, and loose mannish jacket. She smiles back graciously at Giard, and at us, her trim white hair catching the light from the window. She is the focus of Giard’s composition, while all around is evidence of her interests and preoccupations: literature and art, flowers and gardening, and a modest, warm self-presentation that avoids any trace of self-importance.

The graciousness of Sarton’s smile suggests that she has been entirely won over to the process of sitting for Giard. It’s notable that on a page of a journal Giard kept, on which he inscribed the names of writers who had turned down his invitation to join his visual archive of gay and lesbian writers, Sarton was one of those listed among the women. Indeed, she headed the list—but a brisk line runs through her name, indicating a change of heart. Giard was aware that some writers wished to avoid any such label as “gay writer” or “lesbian writer.” As he once wrote, “A certain number declined to be photographed, offering reasons both thin and thoughtful. Some individuals were brusque, others more polite and even introspective, sharing with me their hesitation.” Joan Nestle, cofounder of New York’s Lesbian Herstory Archives, proposes that some writers, such as Sarton, “emboldened by the gay and lesbian civil rights battle, took long journeys in working out what it means to have their work included in the gay and lesbian anthologies of the 1980s.”

When Giard did have a writer’s cooperation, he met his subjects more than halfway. He might buy an out-of-print volume in a secondhand shop, borrow books from friends, or visit the library. He did whatever was necessary to arrive at a sitting mentally armed with a good sense of the writer’s oeuvre. Sarton had a large and varied one. Giard would have put her at ease, and it may even be that her change of heart was occasioned by a friendly intermediary, as was sometimes the case. Just as often, introducing himself and the project in a letter to a prospective writer did the trick. As the archive grew, he was able to tout more and more famous names, so that mentioning his portraits of Edward Albee, Doris Grumbach, María Irene Fornés, or Blanche Wiesen Cook might persuade someone otherwise sitting on the fence to take him up on his offer.

I faced no such dilemma, since we had become friends. Giard—or Bob, as I came to call him—first photographed me in 1980, before Particular Voices took shape. I was anxious sitting for a formal portrait and hadn’t slept well the night before. Bob came to my apartment and only asked that I change my shirt. He remembered me in a striped shirt with a rounded white collar and a skinny tie—would I mind wearing that? He worked quickly and assuredly while my eyelids drooped. The picture that resulted feels as much about my attire as my weary expression. He captured something essentially still and reflective and terribly serious in me. I felt seen through to my soul. He titled it “Man in a Striped Shirt,” although my name is sometimes added in parenthesis. But I rather like the mystery of his title. I was a mystery to myself at the time of the sitting.

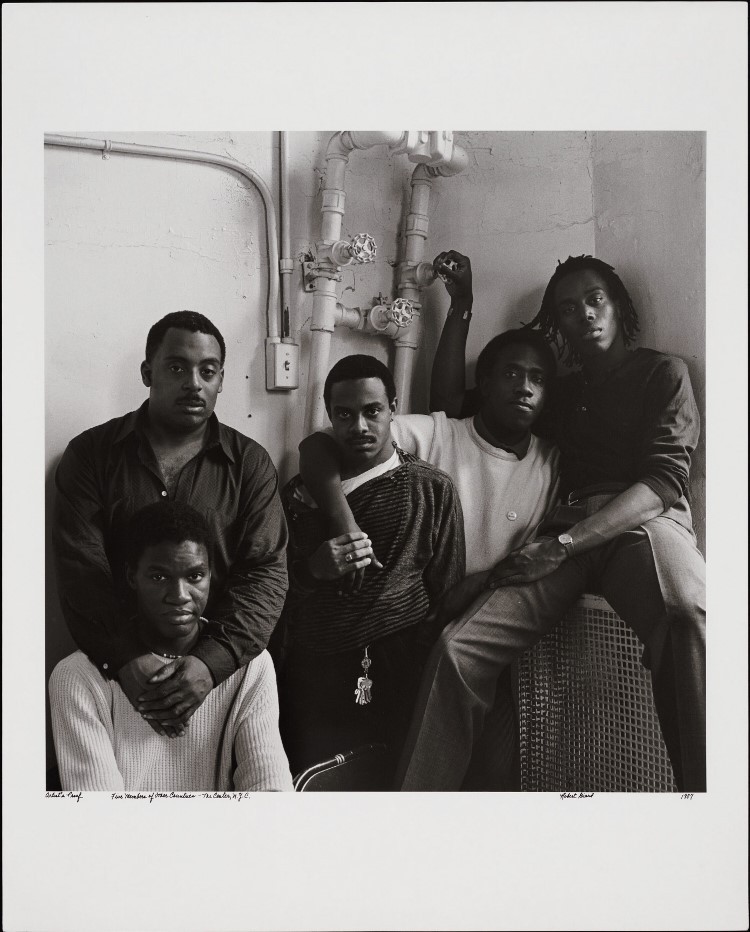

The friend who had accompanied Giard to Hoffman’s As Is was a member of the interracial group Men of All Colors Together, which advocated for an end to homophobia and racism. Through him, Giard met the Haitian American poet and playwright Assotto Saint (Yves Lubin), who subsequently passed Giard on to such writers of color as Samuel R. Delany, Sapphire, and members of the writers collective Other Countries. Such referrals also transpired within regional communities so that Giard’s travels, always on public transit, became pilgrimages to the homes of several LGBTQ writers living within proximity to each other—within a city, between city and suburb, or out in a hinterland where gays and lesbians were thought to barely exist.

Giard was not certifying a canon—neither of writers nor of individual texts—but testifying to the range and diversity of commitment to the word, which had long been a feature of gay and lesbian lives. We queers often find ourselves in books. It was crucial for him to honor marginalized communities whose presence in the mostly white gay male world often went unacknowledged. Such writers rarely had access to the corridors of establishment publishing. His group portrait, “Five Members of Other Countries,” has the casual appearance of friends, young men of color, enclosing each other in loving embrace. Arms are slung around shoulders, hands touch, one friend leans in upon another. The men had finished their workshop in the top floor at the Lesbian and Gay Community Center in Greenwich Village. Carlos Segura remembers being invited with the other four to gather for a group photo, placed in a corner by water pipes, lending the scene the grit of an industrial interior. Each writer looks toward the camera with his own version of trust: left to right, Rodney Dildy, David Frechette, Colin Robinson, Carlos Segura, Donald Woods. Each face stamps its own imprint on the resulting image, hope and faith and perhaps doubt or wonder frozen in time. Other Countries published anthologies, that form which both collects and individuates, giving voice to a fresh generation descended from Langston Hughes and James Baldwin. Among gay men of color, the losses from AIDS were particularly devastating.

If Giard’s project title seems to focus on the narrow binary “gay/lesbian,” in practice his quest to picture emerging queer voices was never exclusionary. He was sensitive to diverse forms of gender expression as he met his subjects on their home turf, deferring to the light that came through their windows. He accepted each subject as a given and their writing as a gift to the larger community. So he gave us a moving double portrait of a couple: Leslie Feinberg, author of the novel Stone Butch Blues (1993), and the poet Minnie Bruce Pratt, whose collection Crime Against Nature (1990), per her Poetry Foundation bio, shares “the story of Pratt’s life after she came out as a lesbian; the ending of her marriage, her unsuccessful battle to keep custody of her children, and her new life as a lesbian.” Posed in a domestic interior, they lounge across a bed, a homey quilt cushioning their reclining clasp. Feinberg’s handsome face stares soberly at the camera, the brush cut atop her head giving him the appeal of a butch dyke, a masculine androgyny that one can imagine kept more than a few people guessing. Minnie Bruce Pratt smiles at us in a slightly conspiratorial way (“Look what I’ve got!”). She reclines under the gentle pressure of Feinberg’s exposed bicep and forearm, while her own arm, folded across her midriff, ends with her hand resting on the quilt. Her wrist displays a decorative charm bracelet; there is a ring upon one of her fingers. If they present as a classically gendered butch-femme couple, of the kind Feinberg might have seen in her youth in the lesbian bars of Buffalo, New York, the alternate tenderness and delight of their paired regard seems least of all a provocation.

Self-taught as a photographer, Giard nevertheless came to his task with deep cultivation in literature. He reminds us of other photographers who memorialized the literary accomplishments of their time by focusing on the men and women whose writing defined the social and intellectual experience of their eras. We think first of Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, 1820–1910), whose photographs of Baudelaire, Théophile Gautier, and George Sand stand beside his other portraits of France’s great 19th-century cultural figures. More recently, the German émigré photojournalist Gisèle Freund took as a principal mission to photograph the great modernist writers between the wars and after—and sometimes in color. She gives us indelible portraits of Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, Walter Benjamin, and Simone de Beauvoir, not forgetting her contribution to the theoretical side of the medium in her astute early text, Photography & Society (translation, 1974). The subject of my own current research, the American George Platt Lynes, at first hoping to become a man-of-letters, ultimately took up the camera and paid homage to writers on both sides of the Atlantic whose reputations were assured and might help advance his own. These included protean figures such as André Gide, Colette, Jean Cocteau, Gertrude Stein, W.H. Auden, T.S. Eliot, and Thomas Mann. Giard joined this pantheon of camera artists who found in the visage of each man- or woman-of-letters a psychological map of infinite variety. There is an echo here of a casual maxim from Gisèle Freund: “What is marvelous about a photograph is that its possibilities are infinite; there aren’t any subjects ‘done to death.’”

Yet in a portrait, death stands at the shoulder of every subject. Giard knew this, and that fact gives many of his photographs an elegiac quality; these are images from the midst of a plague. Some of his portraits–including those of Bo Huston, Sam D’Allesandro, and Arnie Zane, among others–bear harrowing witness to the ravages of that disease. Other subjects—Essex Hemphill, Joe Brainard, Melvin Dixon, Steve Abbott, the list goes on—later died of AIDS-related complications, although Giard’s portraits of them preserve their singular essence. As Giard wrote, “Photography is par excellence a medium expressive of our mortality, holding up, as it does, one time for the contemplation of another time.”

I end then with his portrait of playwright Terrence McNally from 1986. McNally was coming into his own with the success of The Ritz (1975) and Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune (1982). He would go on to write about AIDS, directly or indirectly, in the teleplay Andre’s Mother (1988), and the theatrical stagings Lips Together, Teeth Apart (1991), and Love! Valour! Compassion! (1994). McNally himself had been active in EEGO, and Jonathan Silin, Giard’s lover, recalls, “He was very fond of us—we knew him in a time when things were not going so well professionally with him.” In his portrait, McNally leans into a mantel supporting a single candleholder. A standing lamp echoes the vertical thrust of the silver ornament. Youthful and almost elfin, the hair at his forehead thinning, McNally appeals to us with a suppressed smile. His bare forearms crisscross his chest. A single white button shines at his open collar. His face, arms, and half the wall behind him reflect the light, while the rest of the space falls into massed shadows and somber geometric grays. This tonal drama plays behind McNally who, center stage, holds us in thrall.

At the time Giard took the portrait, McNally’s greatest successes were ahead of him, like The Lisbon Traviata (1989) and Master Class (1995). Luckily, he lived well past the initial trauma of AIDS. But death caught up with him in March; he was felled by COVID-19, by which time, at age 81, he had become an eminence grise in the theater world. (Kramer, too, is now gone; he died in May, at age 84, of non-COVID pneumonia.) Giard was too aware that some of his subjects might have little time left as the AIDS pandemic raged with neither vaccine nor, for a long time, successful drug treatments. And he regretted throughout the two decades of his peripatetic adventures that there were writers he had already missed—and some, because of age, he would likely not get to in time.

In the early days of AIDS, he had wondered if his “own days could prove briefer than most of us are accustomed to anticipating.” Indeed, he left us too soon. In 2002, just shy of turning 63, he died in transit on a commission project, still planning for all those LGBTQ writers who had yet to come before his camera. But what remains is a monumental archive from an era when LGBTQ people stopped hanging their heads in shame, or fear, and came out of the shadows to proudly declare: we are here.

Allen Ellenzweig has written for Art in America, American Photographer, Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide, Tablet, and The Forward. In 1992, Columbia University Press published his landmark illustrated history The Homoerotic Photograph: Male Images from Durieu/Delacroix to Mapplethorpe. His biography of 20th century photographer George Platt Lynes is forthcoming from...

-

Related Articles

-

Related Collections

-

Related Authors

- See All Related Content