From “To Float in the Space Between”

line 22: the graves

line 38: i am me

Later I dreamed I was on a night plane somewhere between the stars and Indianapolis. It was a crow’s sky: ominous, black, sparkling. The man across the aisle, he sounded African, talked to a drowsy white woman about something that frequently featured the words “Obama” and “Oh, Mamma.” It was none of my business. When I looked down from the plane window, I saw cemetery shapes. The African said to the drowsy woman, “It is not often an African marries an American white woman, but when it happens our offspring rule the free world.” I heard him say “cost of living,” and “Yeah,” and “Thank you, Lord” when our plane touched ground.

I visited Indianapolis once in my waking life. Nearly fifteen years after Etheridge Knight’s death, I’d arrived with a satchel of books and questions, invited by Knight’s sister, Eunice, to read my poems at the Etheridge Knight Festival. When I spoke with her about her brother for a few hours in a downtown hotel, she let me record our conversation. She wore a blue headscarf and shared her cigarettes with me. I’d already decided a biography needed to be written and that I would not be the one to write it. My aim was to gather stories his future biographer could use.

I know I should not admit I was dreaming. Vision being what it is in a dream, from a distance I thought the driver awaiting me near baggage claim was none other than three-time NCAA championship coach Bobby Knight. Nearer, I saw he was actually James Whitcomb Riley, the nineteenth-century poet. Age of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, William Cullen Bryant, James Russell Lowell: something sumptuous in a three-word name. Old James Whitcomb Riley struggled a bit dragging my book-heavy bags to the trunk of a sedan longer and blacker than a hearse.

That first trip to Indy, Eunice told me Junior, the family’s nickname for Knight, loved no one more than he loved his mother. After an hour or so Eunice took me to the Crown Hill Cemetery. As the third- or fourth-largest cemetery in the country, it’s a storehouse, a ghost archive to more than 190,000 names. “This will help me get my bearing,” Eunice said from the hilltop where the grand, white columns of James Whitcomb Riley’s tomb loomed at the highest point in the city. She scanned the acres of headstones around us, adjusting her eyeglasses as if they were binoculars as she looked for her brother. She was happy, I think, that I had come, maybe the first ever to come, asking her brother’s story. My bags waited downhill in a pickup truck with an obese, melancholy white woman, Eunice’s daughter-in-law. The plump biracial girl in the backseat was Eunice’s grandchild. Eunice called out plot numbers swinging her cigarette in various directions like a smoldering conductor’s wand, as if she were casting some sort of spell. And I could see she was proud to show me the Riley tomb. It’s possible any out-of-towner visiting Crown Hill for the first time is shown the Hoosier Poet’s resting place. It’s possible countless Indiana children have taken field trips to visit the Hoosier Poet every year since his death in 1916.

That day at least partly explained my driver in the dream. Hoosier made me think of basketball, Bobby Knight in bright red face and sweater berating a referee or a pale player with a crew cut. I imagined James Whitcomb Riley as someone resembling Bobby Knight when Eunice recited the beginning of Riley’s most well known poem to assure me I’d heard of him. I didn’t recognize the poem. I’ve forgotten its lines. It occurred to me: perhaps Bobby Knight had been pretending to be the Hoosier Poet after all.

In the dream, I’d already decided a biography of Etheridge Knight needed to be written and flew to Indianapolis, one of his haunts, to begin it. I’d need to fact-check everything about a man with a slippery relationship to facts. In the bags with me in the dream were files, outlines, interviews, books, journals, essays, and essay fragments. My life was always interrupted when I turned to Knight’s life. Plus, whenever I thought about the specter of writing a biography, I was overcome with fear. Knight was a good talker. I am a good talker, but I have no sense of plot, really. And I generally prefer imagination over research. I had not visited Kentucky, where a biographical plot features the young Knight as a runaway, a Black Huck Finn, and could be researched; I had not visited Korea, where a biographical plot features the young Knight as a seventeen-year-old soldier and runaway, and could be researched; I had not visited the Indiana State Prison where a biographical plot featuring the young Knight as an inmate could be researched; and most significantly, I had not visited Corinth, Mississippi, where Knight was born.

The various plots of Corinth include its namesake, the Greek city-state destroyed by Rome in 146 BC. The plots of Corinth include the year 1854, when a railroad town development called “Cross City” was renamed Corinth. The plots of Corinth include the ghosts of the 473 Rebel soldiers killed in the Second Battle of Corinth during the American Civil War. Sometimes you can have no more than an idea of history’s plots. Plots are filled with dirt and antiquated clothes, with Black landowners just out of earshot of the train whistles and dereliction. The various plots of Corinth include Knight’s mother, Belzora, breathing the wide, free, green air at the turn of the century. “My mother always wore shoes,” Eunice told me. “They raised everything they needed.” Even the whites called her grandfather “Mister Cozart.” This, Eunice said, this was the privilege her brother was born into in 1931. The privilege he wanted all his life, she says.

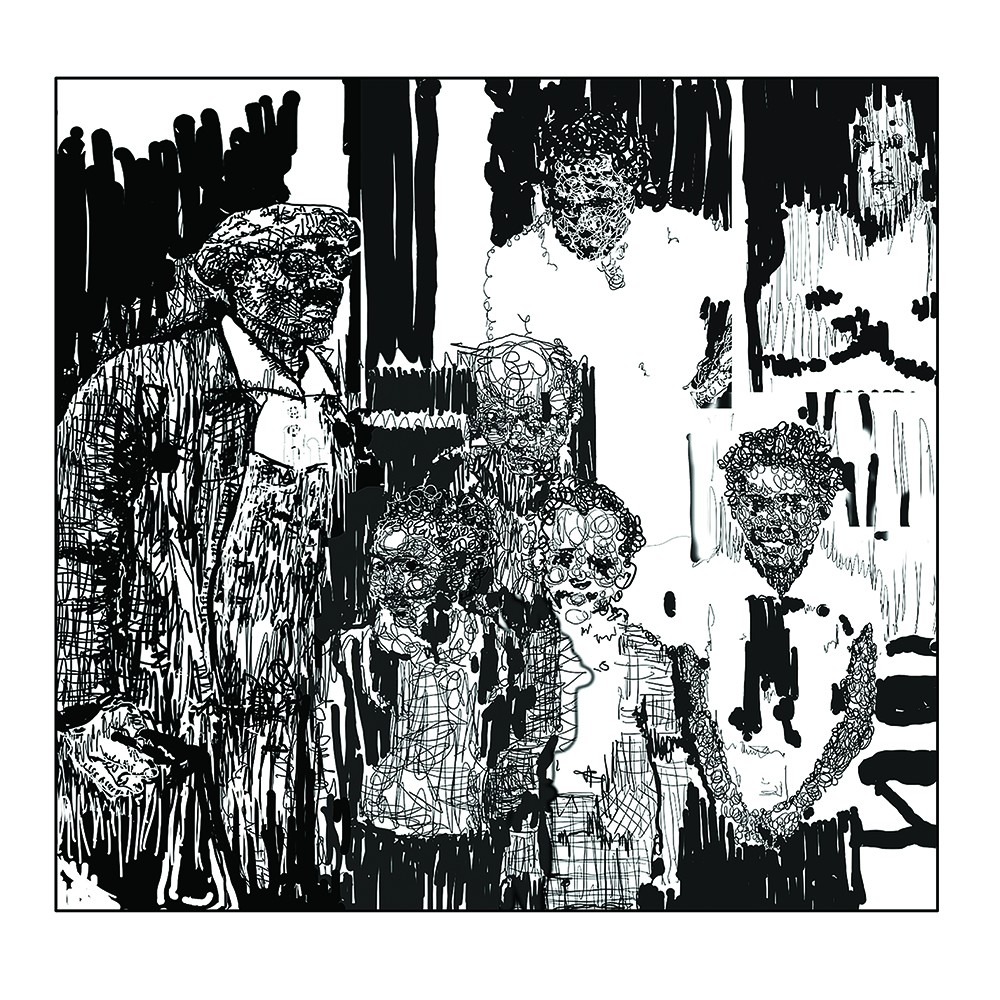

On the back of Etheridge Knight’s Born of a Woman: New and Selected Poems (Houghton Mifflin, 1980), Knight grins from a porch in Mississippi. Gray-haired Mr. Pink Knight and Etheridge wear overalls. Mr. Pink Knight stoops behind three young girls, peering at the camera. Etheridge Knight seems to be looking off, across a field perhaps, caught mid-sentence. The light reflected in the wide lenses of his eyeglasses makes his eyes two white bursts below his newsboy cap. The three girls pose exactly as they would have for an elementary school photo. Mr. Pink Knight seems to be rising from the porch behind him. A woman stands just over his shoulder peering down from the porch with a hand resting on her rotund waist — a pose that is both maternal and amused. A few feet behind her a second, much thinner woman stands with her arms crossed; her face is washed out by the shadows. She seems headless, apparitional, a slightly perturbed ghost in a white dress. They are perhaps the two aunts Knight mentions in “The Idea of Ancestry.”

The photo was taken by Ellen Slack. In the 1988 issue of Painted Bride Quarterly dedicated to Knight, Slack says, “Etheridge had heard that his relative Pink Knight was staying with family in that vicinity, and he wanted me to take some photographs.... No birth records existed for Pink Knight, but by all accounts he had to be at least 110 years old, meaning that he was born in Mississippi shortly after the end of the Civil War.” Knight wanted to record the plots and plights of his oldest living ancestor. He wanted more than an idea of ancestry. A Corinth, Mississippi, plot includes Etheridge Knight smiling in the photo. I once thought a life was simply the accumulation of details. Maybe I think this even now. Knight was often blowing smoke over details. And to write a biography, one would need to gather all that smoke into something solid, something you could hold and turn over in your hands.

Time, patience, and discipline are irrelevant in a dream. I should not admit it was a dream: I reached the same hotel I’d stayed in to interview Eunice years before; I arrived after midnight with a satchel of books, seeking stories of the poet’s life on earth. I did not sleep. There was an old but functional typewriter in my room. The housekeeper said each room had paper and a typewriter. “We like to call them pianos,” she told me. The first time I’d stayed there — when I was awake and real — Eunice said the hotel had been a haunt for Black writers like Mari Evans.

Mari Evans, born the summer of 1919, author of several poetry books, children books, and plays, was still alive somewhere in Indianapolis until March 2017. As further evidence of my lousy research and biographer skills, I didn’t meet her. But in the dream, she worked the desk and wore an ornate water-colored dress, reciting her best-known poem, “I Am a Black Woman,” to anyone who looked like the wrong sort of guest: anyone who was used to talking more than listening, anyone who did not look you in the eye when looking you in the face. She did not hand me my room key until the poem’s dramatic ending:

Beyond all definition stilldefying placeand timeand circumstanceassailedimperviousindestructibleLookon me and berenewed.

I did not sleep. Each time I closed my door or eyes someone showed up to offer a tale about Knight. A woman who looked no more than twenty-five years old wanted to tell me about the day she spent with Knight in 1956. One of my own teachers, Ed Ochester, appeared with a tale of big Beefeater bottles and a whole pig roasting on a spit at the wake Knight held for himself. Poets Robert Bly, Sharon Olds, and Christopher Gilbert showed up to share poems. Jeanne Marie D’Amico stopped by to tell me a version of the story she’d told me when I interviewed her in my waking life. Knight’s leg was amputated after a car wreck in Philadelphia in 1988. In the dream she told me the tracks and scars glowed like half-lit embers in the darkness of his body. His face was swollen and more than half dead, but he still had that voice like burlap soaked in molasses. She handed me a small, silver ring and made me promise to place it on the shy, Black pinky toe of Knight’s remaining foot when I met him.

An old man named Hound Mouth promised I’d be brought to Knight after undertaking a special task. Hound Mouth had spent years gathering the piles of butts left by Etheridge. He organized them into categories: cigarettes smoked in prison, cigarettes smoked after making love, cigarettes smoked in Tennessee, in Massachusetts, in Minnesota, cigarettes smashed under boots, cigarettes tossed into rivers. He had no research to prove they should have been ordered in this way. He’d just held each butt to his nose or to the light and then let his intuition decide its place. My task was to match specific butts to specific poems. I sat with him for what felt like half an eternity just looking at it all. I had a little tape recorder with me. I ate a little corner of Hound Mouth’s ham-and-cheese sandwich. I sat twice as long the next day.

Eventually Hound Mouth gave up on me. In the dream he confessed Knight was still alive and incarcerated in an assisted-living facility across town. We came to a security guard at a small desk in the building’s cavernous lounge. When Hound Mouth told me the guard was Knight’s only son, Isaac BuShie Blackburn-Knight, I blurted almost without thinking, “I liked sons better than children.” “Yeah, me too,” he said, looking down. During my waking visit to Indianapolis Eunice told me someone casually suggested “children” for the end of “The Idea of Ancestry,” so Knight changed it from “sons” to “children.” Sons are not the same as children. Sons are not soft amorphous offspring. Sons are born with knives or pistols; pissing and pointing because they are sons. God only had sons, according to Christians. That tells you some of the trouble with God. Sons are both old and brand new. Sons are miniature men. But children are as generic as people: sometimes horribly innocent, sometimes horribly attractive, and sometimes horrible. Children have no gender. It is false but widely believed that children are universal. It is only true that children are universal if universal means “full of space.” Space is expansive, impermanent, and mysterious. Knight lived with children who were not his children. They had names and nicknames before he met them. But there is little on record about the children because they are thought of as children. The children become invisible. Because the adults are looking elsewhere, but also because the children do not wish to be seen. They were sons before they were children in the poem “The Idea of Ancestry.” Farmers, soldiers, preachers wearing Knight’s name with a princely carriage. He dreamed of them inside the cell. He sat in the dark with a premonition of the damage that would befall his sons. He would have to abandon them to make them stronger. He would have to change them to children.

The suggestion to change the line from “I have no sons” to “I have no children” came before Knight had a son, but now here was his son: half Black, half white, a lobby guard with a goatee thick and woolly as a surgical mask. I could not see his face. In my waking life, I’d wondered often about the boy’s appearance and whereabouts. Did he have his mother’s mouth and nose? Did he have siblings? Did he imagine his father’s ghost was with him when he graduated from high school or college or was admitted to an emergency room with a broken bone? Did he know he was the son of a poet? Had he grown up reading his father’s books? Had he shunned the books stacked tall and smelling of difficulty and tobacco? Had the son seen the photograph of his father in the half-lotus tree yoga pose in a Las Vegas tuxedo shop before the 1987 American Book Award?

Did the son possess photographs of his father’s dark, sleeping head and unzipped, oblivious mouth? Did the son rage or weep in his sleep? He’d be a man now, perhaps with children of his own, but I had done none of the research needed to find him.

In the dream, the watchman was Isaac BuShie Blackburn-Knight. He nodded and let me pass. The building had more floors than there were stars over the city. The elevator ride up was so long I dozed off and dreamed I was being driven north by my little brother. He was telling me a tale about a soldier who had given a testimonial in church one Sunday. He’d been a prisoner of war, bound in the cellar of a farmer and his wife. “I was saved by a black dog, a hound whose master had probably been killed in the war,” the soldier told the dumbstruck congregation, my brother among them.

For a moment I thought the dog was no more than a lean shadow in the corner: a darkness slipping over the antiques and contraptions of my captors. But then the dog pulled the rope from my wrists and ankles. When he touched his cool muzzle to my jaw, I knew he wished to lead me away. I crawled through the cellar window behind him, and then, too tired to rise, followed on my hands and knees through the fields and into a deep, dark forest. Had anyone seen me, they would have thought a dog was following a dog.

We were between borders on a mountain highway when my brother told the story.

Before this trip, I had not been alone with him for that long since childhood. There was a black train in the distance. “I pray for you,” my brother said to me. After a year of marriage he had changed, as a man bound by love or grief is bound to change. Their first child had not survived. He had laid his sorrows down and put on a new name. Sundays now, the preacher came to dine. I wanted to ask a few questions. White fog covered the nose of the car. I was falling into the kind of sleep that requires no darkness. “He reached our church with a look that reminded me of you,” my brother said to me. “We thought he’d come that day to give thanks to God, but he’d come to ask who among us was his kin.”

Born in Columbia, South Carolina, Terrance Hayes earned a BA at Coker College and an MFA at the University of Pittsburgh. In his poems, in which he occasionally invents formal constraints, Hayes considers themes of popular culture, race, music, and masculinity. “Hayes’s fourth book puts invincibly restless wordplay at the...

-

Related Authors

-

Related Collections

- See All Related Content